|

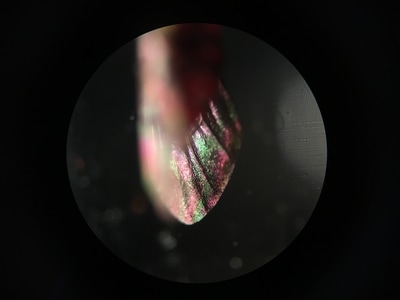

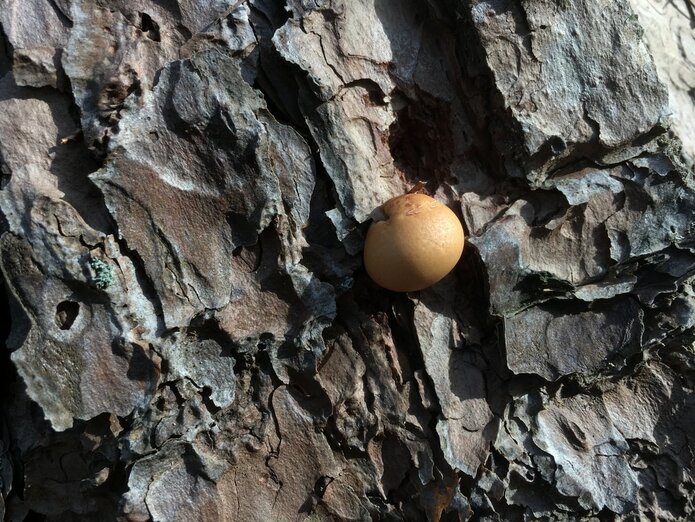

I have been going to the woods as often as I can - two to three times a week - to catch sight and fill my basket with spring mushrooms. Morchella spp. (morels), the holiest of spring mushrooms for mycophagists, is my target. Along the way, I hope to find Helvella spp. and Gyromitra spp. These are all large, fleshy ascomycetes. Recently, I got a copy of Ascomycete Fungi of North America: A Mushroom Reference Guide by Beug, Bessette, and Bessette. The beautiful images in this book have inspired me to find more ascomycetes and not just the large gilled and pored species of Basidiomycota. I am feeling so hopeful now that temperatures are in the 60s and the plants are budding, ready to burst with green foliage. On Saturday, April 15, I explored Middlesex Fells Reservation, which consists of over two thousand acres of water reservoirs, rocky outcrops, and mixed forest, with lots of scraggly patches but some supreme pine and oak forests. I love the soft sponginess of pine needle duff and the erect canopy of the evergreen conifers, or the crispy, crackly old oak leaves that break like ceramic plates underfoot. The smell of dry pine stayed with me all day. Right away I was struck by the dryness. I knew I would have to settle with log rolling, a fruitful activity because you are bound to find something under the moistness of a large, rotting log, but a sad sport when I had been rolling logs all winter long. I was reminded that some biologists might prefer animals because their presence is not ephemeral, not so dependent on rain and temperature like the fruiting bodies of fungi. In these moments, I kick aside a little forest duff to reveal the white mycelium that is literally holding the forest together. I am always dumbfounded when I consider the vast ecological role of fungi: decomposers, sediment stabilizers, symbionts, and pathogens. They are everywhere, and are essential members of nature. I wanted to catch some bees for my partner and deliver them with a triumphant grin. A loving gesture, don't you think? Catching a bee with an aspirator and a falcon tube is no easy task, though. With my tools in place and tube in mouth, I snuck close and then lunged at the resting bees. In the end I captured a green metallic bee and a bee with a red abdomen, as well as a larger, fuzzy bee that I stole from an ant trying to carry it back to its nest. After the bees, I got back to rolling logs. Besides some old pyrenomycetes, my first two finds were Arachnopeziza aurelia (orange cups on oak debris) and Lophodermium pinastri (black apothecia on pine needles). Next up, I rolled over a log and found a nice patch of Xylobolus frustulatus, the ceramic parchment fungus. This fungus looks like white tiles fractured chaotically and filled in with black grout. As the fungus matures, it acquires pastel blush. The final log roll resulted in the biggest prize of the day: my first spring mushroom. I only noticed it by accident, and I am not a primordial mycologist, so I have no idea what this primordium is. Growing on the same log was a gooey slime mold on a stick. Although those primordia were the only fresh fleshy mushrooms that I found, they were a good sign that in a few days and with another rain the forest should be teeming wth spring mushrooms. I was still early, but that's OK, because the forest had endless other sights, smells, and experiences. Walking along the trail, I spotted a large black butterfly with a white border on its wings. It landed and flapped its wings slowly like an accordion, bathing in the sun. I approached to take a picture but it departed when my foot cracked a twig. A moment later, the butterfly attacked! I felt a violent flutter - as violent as a butterfly can be - against my neck, ducked my head, and swung around to confront my attacker, but the butterfly left as quickly as it came. Maybe it thought my neck was a birch stick that it determined was a good place to land and it wasn't aggressively striking my vertebrae to paralyze me. Either way, butterflies have lost all trust. The last find of the day was a very strange polypore. Bubbling out of a dead pine, I found these tough tannish protrusions. To my surprise, there were pores inside. Google quickly gave me the identity of this fungus: Cryptoporus volvatus. This fungus is one of the first to fruit on dead pines. Apparently a little opening develops on the underside of the cover (volva). Beetles enter this opening, dine on the fungus, pick up spores, and transport them to new pines where the spores germinate. I determined that these specimens were very young given the fact that the opening hadn't formed yet and, back at home looking under the microscope, I couldn't find basidia. With spring developing, weather warming, and rain coming, I expect to soon discover some fleshy ascomycetes, all the while enjoying the fresh sights, smells, and budding green of the forest.

1 Comment

Maricel

8/8/2019 08:16:12 pm

Alden, that primordia crust is Xylobolus frustulatus.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

PermalinksProject Introduction Top EdiblesHericium coralloides

Laetiporus sulphureus Morchella americana Polyporus umbellatus Suillus ampliporus Archives

April 2023

Categories |

|

|

Terms of Use, Liability Waiver, and Licensing

The material on aldendirks.com is presented for general informational and educational purposes only, and under no circumstances is to be considered a substitute for identification of an actual biological specimen by a person qualified to make that judgment. Some fungi are poisonous; please be cautious. All images on this website are licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed